Texas Astronomers Lead Major Projects in James Webb Space Telescope’s First Year

19 April 2021

AUSTIN — Astronomers at The University of Texas at Austin are set to lead some of the largest programs in the first year of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), including the largest project overall. Set to launch this Halloween, the telescope will become operational by mid-2022. Altogether, UT astronomers received about 500 hours of telescope time in JWST’s first year.

COSMOS-Webb, a project to map the earliest structures of the universe, is the largest project JWST will undertake in 2022. UT’s Caitlin Casey, assistant professor of astronomy, leads an international team of nearly 50 researchers, along with co-leader Jeyhan Kartaltepe of the Rochester Institute of Technology.

With more than 200 hours of observing time, COSMOS-Webb will conduct an ambitious survey of half a million galaxies. As a “treasury program,” the team will rapidly release their data to the public for use by other researchers.

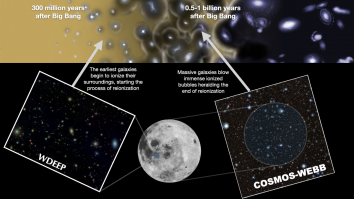

Casey explained that their project will “stare deeply over a large patch of sky, about three times the size of the Moon. Instead of just finding the most distant galaxies, we hope to find them and figure out where they live in the universe, whether it be an ancient cosmic metropolis or a distant cosmic outpost.”

In probing the galaxies’ habitats, they are looking for bubbles showing where the first pockets of the early universe were reionized — that is, when light from the first stars and galaxies ripped apart hydrogen atoms that filled the cosmos, giving them an electric charge. This ended the cosmic dark ages, and began a new era where the universe was flooded with light, called the epoch of reionization. COSMOS-Webb hopes to map the scale of these reionization bubbles.

“COSMOS-Webb has the potential to be ground-breaking in ways we haven’t even dreamt yet,” Casey said. “You don’t know what treasures are there to find until you use an incredible telescope like Webb to stare at the sky for a long time.”

Another major first-year JWST project is led by UT associate professor Steven Finkelstein. The fourth-largest project the telescope will undertake in 2022, it’s called the Webb Deep Extragalactic Exploratory Public (WDEEP) Survey. Finkelstein co-leads a large team along with Casey Papovich of Texas A&M University and Nor Pirzkal of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

In some ways, WDEEP is similar to COSMOS-Webb, Finkelstein said. Both are studying early galaxies, but at different early epochs in the history of the universe.

"Together, the projects COSMOS-Webb and WDEEP are bracketing the epoch of reionization,” Finkelstein said. “So with WDEEP, we’re trying to push to the very beginning of reionization when the earliest galaxies really started to form stars, and begin to ionize the intergalactic medium. Whereas Professor Casey’s program is targeting the end of reionization, looking at the descendants of our galaxies and the bubbles they have created around them.”

In terms of how the projects will be carried out, though, “WDEEP is almost the exact opposite,” Finkelstein said. “While COSMOS-Webb is going very wide to look for the brightest and most massive galaxies, WDEEP is going deep. We are going to pick one place in the sky and stare at it for over 100 hours, following in the footsteps of the original Hubble Deep Field,” he said.

He explained that the goal of WDEEP is to push the frontier in terms of the most distant galaxies detected. The team expects to find 50 or more galaxies at a time less than 500 million years after the Big Bang, which is “a completely unexplored epoch” in the universe’s history, he said. And if they’re lucky, they might find a galaxy at just 270 million years after the Big Bang, or 2% of the universe’s present age of 13.8 billion years.

The goal in finding these most-distant galaxies is to help understand the early universe. “There are a wide range of theoretical predictions for what the universe should look like at these times,” Finkelstein said. “Without observations, these predictions are completely unconstrained. Our goal is to try and pin down those models telling us what the earliest galaxies were like.”

Other UT astronomers lead or co-lead JWST first-year projects on a variety of topics. These include faculty members Brendan Bowler, John Chisholm, Harriet Dinerstein, Neal Evans, and Caroline Morley; postdoctoral researchers Micaela Bagley, Will Best, and Justin Spilker; and graduate student Samuel Factor. The projects include studies of planet formation, the failed stars called brown dwarfs, the chemistry of pre-biotic molecules in newly forming stars, early stages of star formation, the dead stars called planetary nebulae, the formation of massive galaxies in the early universe, and more. Together, they will use about 100 hours of telescope time in the telescope’s first year.

— END —

Media Contact:

Rebecca Johnson, Communications Mgr.

McDonald Observatory

The University of Texas at Austin

512-475-6763

Science Contacts:

Dr. Caitlin Casey, Asst. Professor

Department of Astronomy

The University of Texas at Austin

512-471-3405

Dr. Steven Finkelstein, Assoc. Professor

Department of Astronomy

The University of Texas at Austin

512-471-1483