McDonald Observatory Astronomers Discover New Type of Pulsating White Dwarf Star

1 May 2008

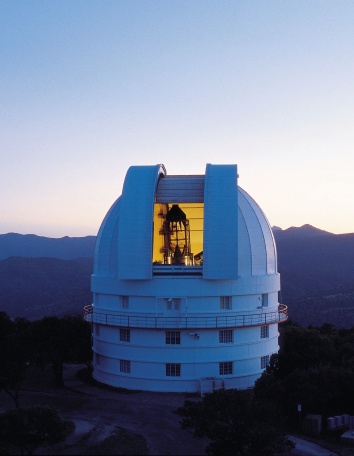

AUSTIN, Texas — University of Texas at Austin astronomers Michael H. Montgomery and Kurtis A. Williams, along with graduate student Steven DeGennaro, have predicted and confirmed the existence of a new type of variable star with the help of the 2.1-meter Otto Struve Telescope at McDonald Observatory. The discovery will be announced in today’s issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Called a “pulsating carbon white dwarf,” this is the first new class of variable white dwarf star discovered in more than 25 years. Because the overwhelming majority of stars in the universe — including the Sun — will end their lives as white dwarfs, studying the pulsations (i.e., variations in light output) of these newly discovered examples gives astronomers a window on an important endpoint in the lives of most stars.

A white dwarf star is the leftover remnant of a Sun-like star that has burned all of the nuclear fuel in its core. It is extremely dense, packing half to 1.5 times the Sun’s mass into a volume about the size of Earth. Until recently, there have been two main types of white dwarfs known: those that have an outer layer of hydrogen (about 80 percent), and about those with an outer layer of helium (about 20 percent), whose hydrogen shells have somehow been stripped away.

Last year, University of Arizona astronomers Patrick Dufour and James Liebert discovered a third type of white dwarf star, still more rare. For reasons that are not understood, these “hot carbon white dwarfs” have had both their hydrogen and helium shells stripped off, leaving their carbon layer exposed. Astronomers suspect these could be among the most massive white dwarfs of all, and are the remnants of stars slightly too small to end their lives in a supernova explosion.

After these new carbon white dwarfs were announced, Montgomery calculated that pulsations in these stars were possible. Pulsating stars are of interest to astronomers because the changes in their light output can reveal what goes on in their interiors — similar to the way geologists study seismic waves from earthquakes to understand what goes on in Earth’s interior. In fact, this type of star-study is called “asteroseismology.”

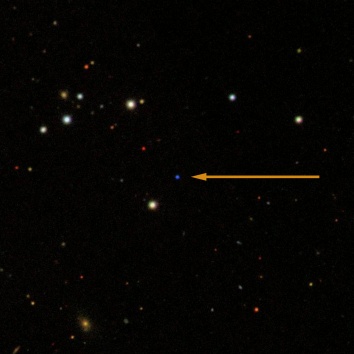

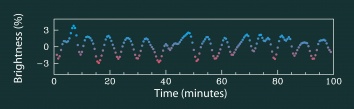

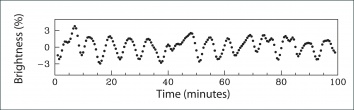

So, Montgomery and Williams’ team began a systematic study of carbon white dwarfs with the Struve Telescope at McDonald Observatory, looking for pulsators. DeGennaro discovered that a star about 800 light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major, called SDSS J142625.71+575218.3, fits the bill. Its light intensity varies regularly by nearly two percent about every eight minutes.

"The discovery that one of these stars is pulsating is remarkably important," said National Science Foundation astronomer Michael Briley. "This will allow us to probe the white dwarf's interior, which in turn should help us solve the riddle of where the carbon white dwarfs come from and what happens to their hydrogen and helium." The research was funded by NSF and the Delaware Asteroseismic Research Center.

The star lies about ten degrees east northeast of Mizar, the middle star in the handle of the Big Dipper. This white dwarf has about the same mass as our Sun, but its diameter is smaller than Earth’s. The star has a temperature of 35,000 degrees Fahrenheit (19,500 C), and is only 1/600th as bright as the Sun.

None of the other stars in their sample were found to pulsate. Given the masses and temperatures of the stars in their sample, SDSS J142625.71+575218.3 is the only one expected to pulsate based on Montgomery’s calculations.

The astronomers speculate that the pulsations are caused by changes in the star’s carbon outer envelope as the star cools down from its formation as a hot white dwarf. The ionized carbon atoms in the star’s outer layers return to a neutral state, triggering the pulsations.

There is a chance that the star’s variations might have another cause. Further study is needed, the astronomers say. Either way, studying these stars will shed light on the unknown process that strips away their surface layers of hydrogen and helium to lay bare their carbon interiors.

— END —

Additional Media Contact:

Diane Benegas

National Science Foundation

703-292-4489